|

|||

|

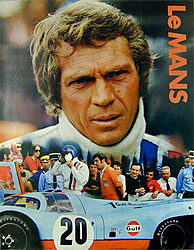

[Around 20 sports car / racing / movie / McQueen / pizza fans came out for our first AONE Pizza and a Movie Night of the off-season on Saturday, November 19th. They were greeted by the aroma of popping corn to set up an atmosphere of authenticity (even though the "theatre" was a converted living room). When just about everyone had arrived, we ran our feature (the 1971 film Le Mans) on schedule at 4:30. The pizzas (again provided by Dedham's High Street Pizza) arrived at around 6:00 and the gang attacked them with relish (well, you know what I mean). As we sat back down, we played the high-speed chase scene from McQueen's Bullitt, which is the one that started the entire car chase genre. Finally, we screened the recent "making-of" documentary entitled Steve McQueen: The Man and Le Mans. [When Peter left for home, he and I agreed to write contrasting Siskel & Ebert-style reviews of the movies we had watched. But when Peter's arrived I immediately realized that there was no way that anything I would write could possibly come close, and I apologized for not holding up my end of the bargain. Our thanks go out to Peter and also to Phil Bostwick, who let us borrow his three McQueen blu-ray disks but was unable to join us this time. Without further ado, we hope you enjoy the excellent and informative report below.

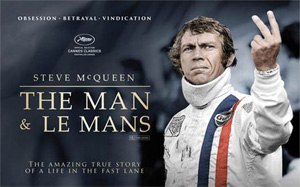

When Le Mans came out in 1971, the New York Times said that: "Dramatically, the picture is a bore." Phil Bostwick, AONE's organizer of Cape Crusades and our resident historian of cinema and sports car racing, believes that Le Mans is not as interesting a film as the 2015 documentary about it, Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans. Given the poor critical reception

The subject of Le Mans is precisely that: the 24 Hours of Le Mans, the storied 24-hour endurance race held over a long weekend in the middle of June every year since 1923 (with a few years' interruption during the 1940s). Proponents of other storied races, like the Indianapolis 500 or the Grand Prix of Monaco, might argue, but in fact Le Mans is the greatest of all auto races, the ultimate test of drivers, cars, and teams. Unlike at Indianapolis, the track turns in both directions, and unlike at Monaco, the winner of the pole position in qualifying is not almost guaranteed to win the race—far from it. The greatest names among auto manufacturers have taken turns dominating Le Mans, from Bentley and Ferrari to Ford and Audi, by way of Alfa Romeo. Jaguar's domination in the 1950s helped bring disk brakes to all modern cars. Porsche's in the 1970s and 1980s helped standardize turbocharging on modern high performance (and even not so high performance) street cars. Drivers like Briggs Cunningham, But Le Mans isn't just a race. Like Indianapolis and Monaco it is an event. A quiet area of rural France takes on a completely different atmosphere during the better part of one week. There are traffic jams galore. Special trains. All available lodgings fill. There are campers: camping cars, camping trailers, small and large tents, and people sleeping on the ground, with or without a sleeping bag. There are carnival rides and barkers and concessions. And the press turns out in all of its persistence.

The film Le Mans captures the flavor of all of this. It is not just a racing movie but a movie about all the aspects of the event that is Le Mans. The race itself (which uses actual footage of the 1970 edition of the race) is an important part of the film, including a fictional finish with two Ferraris and two Porsches all on the same last lap (and one race-result-altering tire failure). But just as important as the race itself is how the film captures the dynamic of being a driver in such a race: from living with the real danger of crippling or deadly crashes; to the widow (forgettably acted by Elga Andersen) who, in spite of the tragic death of her husband the previous year, can't keep away from the spectacle; to the experienced driver (played by Fred Haltiner) who makes his wife's day when he tells her that this race will be his last, that it

While a documentary about Le Mans could capture the action on the track and the "scene" of the camping grounds, the concessions, and the carnival rides (including a karting track), it could not easily capture those behind-the-scenes dynamics of racing life. Nor could it capture what is the film's greatest strength: its powerful evocation of the feeling of adrenalin and euphoria of driving a great car in its ideal environment. As one of the drivers explains in Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans, to drive a car in perfect condition on a good race track is the greatest feeling there is; it is like a ballet; it is a thing of beauty. Above all, Steve McQueen wanted Le Mans to capture and convey that euphoria, and the film succeeded. John Frankenheimer revolutionized auto race filming when he made Grand Prix by putting actual actors into race cars and

Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans explains McQueen's obsession with that euphoria. Much of the film follows his grown-up youngest son, Chad, as he explains both his father's and his own love of fast cars. At one moment Chad relates how during the filming of Le Mans, his father—at the wheel of a 917—took young Chad on his lap, and while driving around the circuit, had Chad steer the car. As Chad explains, one never forgets an experience like that. But Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans also conveys the cost and the danger of experiencing that euphoria. Le Mans shows two horrendous accidents (of a Ferrari and of McQueen's 917), but much of these accidents are in slow motion, reminding viewers that we're watching a film, not a real driver maybe get really killed in an actual race. In Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans, though, we learn that Chad walks with a limp because, as his mother tells the camera, he had "kissed the wall at Daytona," and Chad himself explains that he wears shades all the time because his eye still hadn't straightened out from the accident. Niele Adams McQueen, Steve's first wife, concludes with a list of all McQueen lost from filming Le Mans (which went months over schedule and $1.5 million over its original $6 million budget): his marriage (in part due to serial womanizing), his production company (Solar Productions), his relationship with business partner Robert Relyea, and his working relationships with director John Sturges and screenwriter Alan Trustman. Chad adds to the list that his father even lost his love for fast cars. But perhaps the most heart-breaking moment in Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans comes when we learn of the accident

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

Le Mans received when it appeared, the organizers of AONE's November 19 Steve McQueen/Le Mans double feature film night had low expectations for the original film. We expected the highlight of the evening to be the new documentary. We programmed Le Mans first because the later film makes far more sense to a viewer familiar with the earlier one. Also, as the French say, a bottle of wine should never make you regret the previous one, and hence one serves the better wine last. So too, we felt, with the films. However, one is often pleasantly surprised when expectations are low. Although I had seen Le Mans at least twice before, it was a long time since I had seen it on a screen as large as the one provided by AONE's Casa Pratt Theatre Dedham, and I came away from the viewing impressed that Le Mans is a possibly flawed but nevertheless tremendous work of art.

Le Mans received when it appeared, the organizers of AONE's November 19 Steve McQueen/Le Mans double feature film night had low expectations for the original film. We expected the highlight of the evening to be the new documentary. We programmed Le Mans first because the later film makes far more sense to a viewer familiar with the earlier one. Also, as the French say, a bottle of wine should never make you regret the previous one, and hence one serves the better wine last. So too, we felt, with the films. However, one is often pleasantly surprised when expectations are low. Although I had seen Le Mans at least twice before, it was a long time since I had seen it on a screen as large as the one provided by AONE's Casa Pratt Theatre Dedham, and I came away from the viewing impressed that Le Mans is a possibly flawed but nevertheless tremendous work of art. Phil Hill, Graham Hill, Jacky Ickx, Derek Bell, Olivier Gendebien, Paul Frère, and Tom Kristensen became famous mastering the challenges of the Circuit de la Sarthe, to use the official name of the track (much of which uses ordinary roads that are open to normal traffic the remaining 51 weeks of the year). The circuit's Mulsanne Straight is so famous that Bentley names its highest performance model after it. The best-designed cars at Le Mans have to be aerodynamic enough to hold speeds above 240 mph on the Mulsanne Straight, but they have to have the handling to maintain speed through the tight corners on other parts of the circuit. Designers have to work a fine line between the slippery aerodynamics needed to reach such high top speeds and the down force that helps control the cars in the corners. The winning cars have to be light and fast enough to keep ahead of the other cars in their class, but they have to be solid and sturdy enough to hold together for 24 hours straight of racing. And the drivers have to have stamina and nerves of steel to match.

Phil Hill, Graham Hill, Jacky Ickx, Derek Bell, Olivier Gendebien, Paul Frère, and Tom Kristensen became famous mastering the challenges of the Circuit de la Sarthe, to use the official name of the track (much of which uses ordinary roads that are open to normal traffic the remaining 51 weeks of the year). The circuit's Mulsanne Straight is so famous that Bentley names its highest performance model after it. The best-designed cars at Le Mans have to be aerodynamic enough to hold speeds above 240 mph on the Mulsanne Straight, but they have to have the handling to maintain speed through the tight corners on other parts of the circuit. Designers have to work a fine line between the slippery aerodynamics needed to reach such high top speeds and the down force that helps control the cars in the corners. The winning cars have to be light and fast enough to keep ahead of the other cars in their class, but they have to be solid and sturdy enough to hold together for 24 hours straight of racing. And the drivers have to have stamina and nerves of steel to match. is time to retire; to that same wife (played by Louise Edlind, later in life a Member of the Swedish Parliament), who struggles between showing her relief and continuing to appear supportive of what her husband clearly loves to do: race the world's fastest cars. The film shows such mundane things as what the drivers do while their co-drivers are behind the wheel (the dinner buffet spread available to the drivers looks wonderful!, and the drivers' trailers are cozy). One thread that runs throughout the film is the friendly but deadly serious rivalry between the top Porsche driver, played by McQueen, and the top Ferrari driver, played by Siegfried Rauch, and one of the film's iconic moments occurs at the end when McQueen, having finished second, gives Rauch, who finished third, a teasing but dead-pan British—i.e. two-fingered—finger, to which Rauch responds by breaking into a smile.

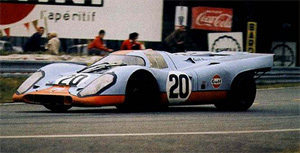

is time to retire; to that same wife (played by Louise Edlind, later in life a Member of the Swedish Parliament), who struggles between showing her relief and continuing to appear supportive of what her husband clearly loves to do: race the world's fastest cars. The film shows such mundane things as what the drivers do while their co-drivers are behind the wheel (the dinner buffet spread available to the drivers looks wonderful!, and the drivers' trailers are cozy). One thread that runs throughout the film is the friendly but deadly serious rivalry between the top Porsche driver, played by McQueen, and the top Ferrari driver, played by Siegfried Rauch, and one of the film's iconic moments occurs at the end when McQueen, having finished second, gives Rauch, who finished third, a teasing but dead-pan British—i.e. two-fingered—finger, to which Rauch responds by breaking into a smile. filming them at race speeds (rather than filming them at safe, slow speeds and then speeding up the film). Le Mans did the same and more: it also put film cameras into actual competitive race cars (including the same Porsche 908 in which McQueen had finished second at Sebring in 1970) and ran them in the actual race. Few members of AONE have attended (or likely ever will be able to attend) the 24 Hours of Le Mans, and even fewer have piloted or ever will pilot a Porsche 917, in anger or otherwise. Seeing Le Mans is the next best thing. And while most streetable Alfa Romeos are a far cry from the monster that is a Porsche 917, every AONE member who has experienced the bliss of driving a well-sorted Alfa on a track or on an open country road on a sunny day or a moonlit summer evening knows the euphoria that Le Mans conveys. It is what the sport and our hobby are all about.

filming them at race speeds (rather than filming them at safe, slow speeds and then speeding up the film). Le Mans did the same and more: it also put film cameras into actual competitive race cars (including the same Porsche 908 in which McQueen had finished second at Sebring in 1970) and ran them in the actual race. Few members of AONE have attended (or likely ever will be able to attend) the 24 Hours of Le Mans, and even fewer have piloted or ever will pilot a Porsche 917, in anger or otherwise. Seeing Le Mans is the next best thing. And while most streetable Alfa Romeos are a far cry from the monster that is a Porsche 917, every AONE member who has experienced the bliss of driving a well-sorted Alfa on a track or on an open country road on a sunny day or a moonlit summer evening knows the euphoria that Le Mans conveys. It is what the sport and our hobby are all about. sustained by race car driver David Piper during the filming of additional scenes: his 917 just suddenly "went"; it hit the Armco, the car disintegrated almost entirely, and as the voice-over explains, Piper was left strapped to his seat, which was still bolted, essentially, to the engine. Underlining the driver's vulnerability, the screen at the same time shows the humongous V-12 engine of the wrecked Porsche 917 with the seat and Piper's custom-fit red seat cushion still connected at the front. The film goes on to explain that Piper was flown to a hospital, where his right leg was amputated four inches below the knee. At this point, the screen shows Piper as he is today arise from the seat at which he had been seated throughout all his interview scenes and hobble off screen. We next see Piper hobble in front of and open a garage door, revealing his own 917, which the final credits tell us Piper still drives in vintage racing. Few cinematic sequences more powerfully evoke the complex emotions and feelings associated with motor racing: the danger, the courage and persistence (to the point even of foolishness), and the allure. Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans is a powerful complement to Le Mans, the earlier film. It helps us to understand why McQueen had to make that film and what he hoped it would communicate. Le Mans may have been "Dramatically … a bore" to the reviewer for the New York Times, but it is not true that it does not have a plot. It does: people come to Le Mans, there is a race, and the people go home. What Le Mans does not have is a Hollywood plot, which unfortunately is what movie-goers expected from a film starring Steve McQueen. Great artists from Shakespeare to Beethoven, from Monet to Miles Davis defied expectations and broke and transcended the conventions and restrictions that prevailed in their day and in the process produced great art, and Le Mans—even if, arguably, flawed—is great art.

sustained by race car driver David Piper during the filming of additional scenes: his 917 just suddenly "went"; it hit the Armco, the car disintegrated almost entirely, and as the voice-over explains, Piper was left strapped to his seat, which was still bolted, essentially, to the engine. Underlining the driver's vulnerability, the screen at the same time shows the humongous V-12 engine of the wrecked Porsche 917 with the seat and Piper's custom-fit red seat cushion still connected at the front. The film goes on to explain that Piper was flown to a hospital, where his right leg was amputated four inches below the knee. At this point, the screen shows Piper as he is today arise from the seat at which he had been seated throughout all his interview scenes and hobble off screen. We next see Piper hobble in front of and open a garage door, revealing his own 917, which the final credits tell us Piper still drives in vintage racing. Few cinematic sequences more powerfully evoke the complex emotions and feelings associated with motor racing: the danger, the courage and persistence (to the point even of foolishness), and the allure. Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans is a powerful complement to Le Mans, the earlier film. It helps us to understand why McQueen had to make that film and what he hoped it would communicate. Le Mans may have been "Dramatically … a bore" to the reviewer for the New York Times, but it is not true that it does not have a plot. It does: people come to Le Mans, there is a race, and the people go home. What Le Mans does not have is a Hollywood plot, which unfortunately is what movie-goers expected from a film starring Steve McQueen. Great artists from Shakespeare to Beethoven, from Monet to Miles Davis defied expectations and broke and transcended the conventions and restrictions that prevailed in their day and in the process produced great art, and Le Mans—even if, arguably, flawed—is great art.